Headwaters

Welcome everyone to this blog!

I am Gordon and over the next few weeks, this blog will cover issues relating water and food in Africa, of which I feel is very current and salient. Amidst the great breadth of topics, I plan to focus on the following: food production, climate change, food security and the future of farming. Given the varied landscapes and environments in Africa, I would use a select few case studies and focus on different regions for the subsequent posts.

Setting the stage

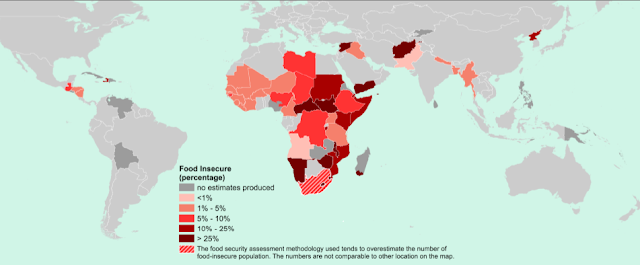

Globally, agriculture is responsible for most freshwater consumption, accounting for “70% of freshwater withdrawals from rivers and aquifers” (UNCTAD, 2011, p.1). Such close links between water and agriculture entails that water is an important part of food production and security (FAO, 2008). While Africa as a whole does not suffer from a lack of water resources, it is estimated only 4% of arable land is irrigated (Giordano, 2005). Compounded by the low per capita agricultural production, many people in Africa suffer from malnutrition and “severe food insecurity” and this is particularly dire in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 237 million people suffered from hunger in 2017 (UNDP, 2019).

Figure 1. Choropleth map of food insecurity in the world by population percentage. Note the high rates in the African continent (FAO, 2017).

The current trends of rapidly growing populations and warmer temperatures due to climate change only serve to further threaten food security in the future (Funk & Brown, 2008). For example, a 2030 food yield model by Funk & Brown (2008), after considering possible rainfall changes, projected that Western and Eastern Africa had lower agricultural yield per hectare. Given how much of Sub-Saharan Africa uses rainfall agriculture and the already large variability in precipitation, more infrequent but intense rainfall could have severe ramifications on food security (Funk & Brown, 2008).

A sinking situation?

With such scenarios looming ahead, a number of solutions to alleviate food security have been proposed. The “green revolution” which occurred in parts of Asia such as India and China, utilised intensive groundwater irrigation methods to increase agricultural output (UNCTAD, 2011). With more renewable groundwater resources (estimated by FAO [2003]) than China and India, could Sub-Saharan Africa follow a similar trajectory? Others have pointed towards the possibility of larger scale commercial farming compared to the current small-holder farming to improve productivity. And what of the thoughts and opinions of the farmers themselves?

Over the next few weeks I will be revisiting such questions in greater detail so do stay tuned!

I am Gordon and over the next few weeks, this blog will cover issues relating water and food in Africa, of which I feel is very current and salient. Amidst the great breadth of topics, I plan to focus on the following: food production, climate change, food security and the future of farming. Given the varied landscapes and environments in Africa, I would use a select few case studies and focus on different regions for the subsequent posts.

Setting the stage

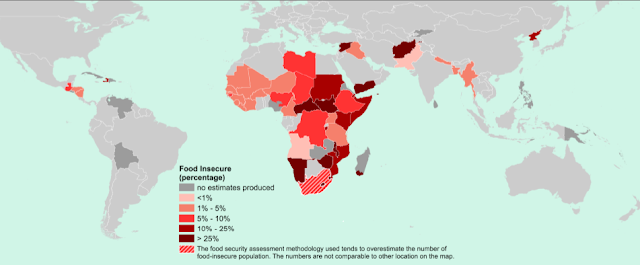

Globally, agriculture is responsible for most freshwater consumption, accounting for “70% of freshwater withdrawals from rivers and aquifers” (UNCTAD, 2011, p.1). Such close links between water and agriculture entails that water is an important part of food production and security (FAO, 2008). While Africa as a whole does not suffer from a lack of water resources, it is estimated only 4% of arable land is irrigated (Giordano, 2005). Compounded by the low per capita agricultural production, many people in Africa suffer from malnutrition and “severe food insecurity” and this is particularly dire in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 237 million people suffered from hunger in 2017 (UNDP, 2019).

Figure 1. Choropleth map of food insecurity in the world by population percentage. Note the high rates in the African continent (FAO, 2017).

The current trends of rapidly growing populations and warmer temperatures due to climate change only serve to further threaten food security in the future (Funk & Brown, 2008). For example, a 2030 food yield model by Funk & Brown (2008), after considering possible rainfall changes, projected that Western and Eastern Africa had lower agricultural yield per hectare. Given how much of Sub-Saharan Africa uses rainfall agriculture and the already large variability in precipitation, more infrequent but intense rainfall could have severe ramifications on food security (Funk & Brown, 2008).

A sinking situation?

With such scenarios looming ahead, a number of solutions to alleviate food security have been proposed. The “green revolution” which occurred in parts of Asia such as India and China, utilised intensive groundwater irrigation methods to increase agricultural output (UNCTAD, 2011). With more renewable groundwater resources (estimated by FAO [2003]) than China and India, could Sub-Saharan Africa follow a similar trajectory? Others have pointed towards the possibility of larger scale commercial farming compared to the current small-holder farming to improve productivity. And what of the thoughts and opinions of the farmers themselves?

Over the next few weeks I will be revisiting such questions in greater detail so do stay tuned!

I like how you sectioned this post and set the stage for your blog! The image you provided is helpful with understanding food insecurity in Africa.

ReplyDelete