Beneath the surface

In this blog post, I will be covering some possible misconceptions people might have about Africa and a broader perspective surrounding water and food. Irrigation may seem like a simple answer to increasing productivity on the African continent where food productivity per capita is the lowest in the world, but there are far more complex issues at hand that discourage adoption of irrigation techniques. Food is also tied to development in societies dominated by agriculture.

News about Africa is seemingly dominated by negativity, insecurity and the plight of Africans (Nothias,2016). Whether how veritable such information is, they can dominate certain representations and paint a distorted picture. Regarding water and food, Nikoloski, Christiaensen and Hill (2018) state that a predominant perception of impacts to agriculture in Africa is drought. However, other occurrences such as floods, landslides and price fluctuations can also bring about significant detriment (Nikoloski,Christiaensen & Hill, 2018). Similarly, irrigation in the African context also brings with it many different narratives and goes beyond mere usage of water for agriculture. In the following sections, I will provide some perspectives relating water supply, food and development.

1. Is there water scarcity?

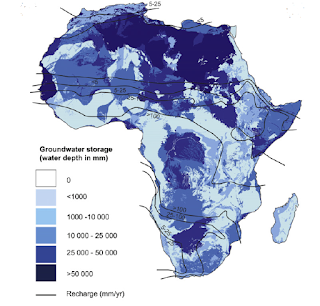

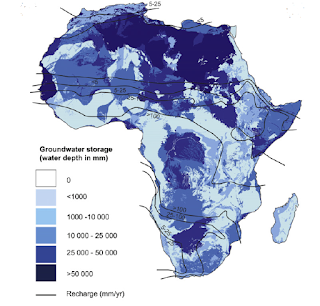

Much has been said about Africa’s groundwater potential. Holding an estimated 0.66 million km3 of groundwater reserves (Macdonald et al., 2012), utilising groundwater seems like a straightforward solution to increasing agricultural productivity. For example, towards the Egypt, Chad, Sudan and Libya share the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer system, the “largest known fossil aquifer” discovered, with an estimate of 457,570 km3 of groundwater storage (Quadri, 2019). Egypt and Libya alone have accounted for close to 40 km3 of groundwater extraction for irrigation and drinking water (Quadri, 2019). Unfortunately, the varying landscapes and geology throughout Africa dictates that groundwater is unevenly distributed.

Figure 1. An overview of groundwater storage in Africa (Macdonald et al., 2012)

The thematic map above showcases the distribution of groundwater supplies. However, even countries in Sub-Saharan Africa such as Kenya and Tanzania, which have relatively low estimated groundwater reserves compared to the aforementioned in North Africa, do experience seasonal rainfall for rain-fed agriculture.

Furthermore, while 4% is commonly cited as land irrigated in Sub-Saharan Africa, that number may be an underestimation (Giordano, 2005). Groundwater has been used traditionally, often in small scale farming and used to mitigate droughts (Giordano, 2005). Beyond crop production, groundwater remains an essential element for rearing of livestock, especially in arid conditions (Giordano, 2005). Therefore, Africa may not suffer from physical water scarcity as certain narratives depict. A better question to ask might be “why is groundwater not more utilised?” instead and that is partly related to economic water scarcity.

2. Economic water scarcity

Economic water scarcity is the lack of capital or infrastructure to access water resources to meet the demands of a population (The Water Project, 2019). Farmers, with their own knowledge of the land and water policies, possibly avoid increased irrigation due to low returns (Giordano, 2005). A common perception regarding groundwater extraction is its exorbitant cost, whereby the low yields found in “fractures or shallow aquifers” discourage investment as a source for irrigation (Giordano, 2005, p. 622). Moreover, fossil groundwater supplies at great depths have large pumping costs attached (Giordano, 2005). Additionally, increasing productivity is multi-faceted, and while sufficient water supplies is certainly a pre-requisite, many other factors impede the use of this resource. If irrigation sites are located away from markets, this further increases the costs and reduces remuneration from farming (Giordano, 2005). Many bureaucratic and legal issues also remain that hamper greater irrigation, such as procuring the necessary equipment and obtaining financing (Mwamakamba et al., 2017). Thus, if transport links, market access, infrastructure and policies for groundwater extraction are inadequate, they can impede the implementation of increased irrigation for greater agricultural output.

3. Agriculture and development

Perhaps increased investment in the aforementioned would provide greater buy-in and profitability for farmers. These profits in turn, help to sustain continued future investment for agriculture inputs.

This is not only related to food security, but development for African states, especially for those whose economies are dominated by it. McCullough (2019) notes that agriculture is the prevalent source of income for most people in Sub-Saharan Africa and much nonfarm agriculture work is related to agriculture.

Figure 2. Thematic map showing GDP per capita and what percentage agriculture constitutes for African countries (Agriculture in Africa, 2013).

The above graphic shows the relative dependence of countries on agriculture and countries such as Somalia and Ethiopia still derive more than 45% of their GDP from agriculture. Development of the rural economy is crucial for the lowering of poverty (Byerlee, de Janvry& Sadoulet, 2009). Increasing productivity not only raises the income of farmers, but could lower food prices and make food more accessible to the poor (Byerlee, de Janvry & Sadoulet, 2009), contributing to the alleviation of food insecurity and malnutrition that plagues many in Africa.

Conclusion

While Africa does not suffer from physical water scarcity, there remains many barriers that complicate access to groundwater where available. Tackling such impediments remain vital to increasing productivity and reducing poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition, all of which are important elements of development.

1. Is there water scarcity?

Much has been said about Africa’s groundwater potential. Holding an estimated 0.66 million km3 of groundwater reserves (Macdonald et al., 2012), utilising groundwater seems like a straightforward solution to increasing agricultural productivity. For example, towards the Egypt, Chad, Sudan and Libya share the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer system, the “largest known fossil aquifer” discovered, with an estimate of 457,570 km3 of groundwater storage (Quadri, 2019). Egypt and Libya alone have accounted for close to 40 km3 of groundwater extraction for irrigation and drinking water (Quadri, 2019). Unfortunately, the varying landscapes and geology throughout Africa dictates that groundwater is unevenly distributed.

Figure 1. An overview of groundwater storage in Africa (Macdonald et al., 2012)

The thematic map above showcases the distribution of groundwater supplies. However, even countries in Sub-Saharan Africa such as Kenya and Tanzania, which have relatively low estimated groundwater reserves compared to the aforementioned in North Africa, do experience seasonal rainfall for rain-fed agriculture.

Furthermore, while 4% is commonly cited as land irrigated in Sub-Saharan Africa, that number may be an underestimation (Giordano, 2005). Groundwater has been used traditionally, often in small scale farming and used to mitigate droughts (Giordano, 2005). Beyond crop production, groundwater remains an essential element for rearing of livestock, especially in arid conditions (Giordano, 2005). Therefore, Africa may not suffer from physical water scarcity as certain narratives depict. A better question to ask might be “why is groundwater not more utilised?” instead and that is partly related to economic water scarcity.

2. Economic water scarcity

Economic water scarcity is the lack of capital or infrastructure to access water resources to meet the demands of a population (The Water Project, 2019). Farmers, with their own knowledge of the land and water policies, possibly avoid increased irrigation due to low returns (Giordano, 2005). A common perception regarding groundwater extraction is its exorbitant cost, whereby the low yields found in “fractures or shallow aquifers” discourage investment as a source for irrigation (Giordano, 2005, p. 622). Moreover, fossil groundwater supplies at great depths have large pumping costs attached (Giordano, 2005). Additionally, increasing productivity is multi-faceted, and while sufficient water supplies is certainly a pre-requisite, many other factors impede the use of this resource. If irrigation sites are located away from markets, this further increases the costs and reduces remuneration from farming (Giordano, 2005). Many bureaucratic and legal issues also remain that hamper greater irrigation, such as procuring the necessary equipment and obtaining financing (Mwamakamba et al., 2017). Thus, if transport links, market access, infrastructure and policies for groundwater extraction are inadequate, they can impede the implementation of increased irrigation for greater agricultural output.

3. Agriculture and development

Perhaps increased investment in the aforementioned would provide greater buy-in and profitability for farmers. These profits in turn, help to sustain continued future investment for agriculture inputs.

This is not only related to food security, but development for African states, especially for those whose economies are dominated by it. McCullough (2019) notes that agriculture is the prevalent source of income for most people in Sub-Saharan Africa and much nonfarm agriculture work is related to agriculture.

Figure 2. Thematic map showing GDP per capita and what percentage agriculture constitutes for African countries (Agriculture in Africa, 2013).

The above graphic shows the relative dependence of countries on agriculture and countries such as Somalia and Ethiopia still derive more than 45% of their GDP from agriculture. Development of the rural economy is crucial for the lowering of poverty (Byerlee, de Janvry& Sadoulet, 2009). Increasing productivity not only raises the income of farmers, but could lower food prices and make food more accessible to the poor (Byerlee, de Janvry & Sadoulet, 2009), contributing to the alleviation of food insecurity and malnutrition that plagues many in Africa.

Conclusion

While Africa does not suffer from physical water scarcity, there remains many barriers that complicate access to groundwater where available. Tackling such impediments remain vital to increasing productivity and reducing poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition, all of which are important elements of development.

Comments

Post a Comment